3 Elements of Development Programs That Last

International education projects can continue to change lives long after the formal project has ended. The secret lies in creating initiatives that become part of the fabric of national education policy.

“Building the capacity of our partner governments to maintain programs is really fundamental to any sort of systemic change,” says EDC’s Rachel Christina.

But creating sustainable programs isn’t a simple process. Political priorities change; key stakeholders come and go. Funding sources vary, too.

So what does it take to create educational programs that work—and last? Three EDC experts share their lessons from the field.

1. Build ministry partnerships

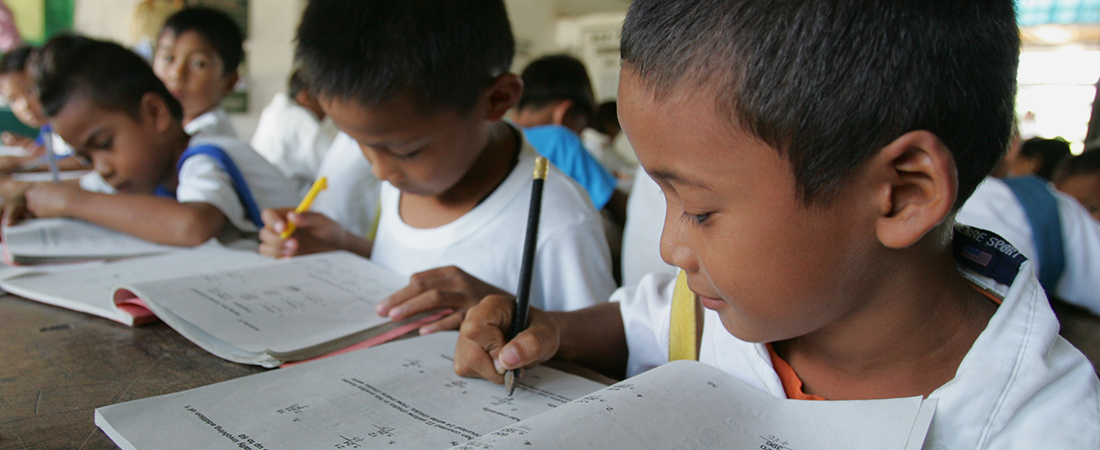

For an education project to thrive beyond its stated end date, support from the government agencies it serves is critical. EDC’s Lisa Hartenberger Toby draws on her experiences in the Philippines, where EDC’s Basa Pilipinas basic literacy project benefited from a close relationship with that country’s Department of Education (DepEd).

“You have to know what the Ministry’s objectives are,” she says. “Then you have to continually reinforce that you are working toward a common goal.”

Regular meetings with national, regional, and local staff as well as involving DepEd staff on key project tasks—including reviewing materials and conducting teacher trainings—were key to nurturing long-term relationships.

Also important? A deep knowledge of DepEd policy and practice, which allowed Basa Pilipinas to complement, rather than compete with, the Philippines’ existing national educational priorities.

All of this work is making a difference in building a sustainable program. DepEd is now using the project’s literacy materials in classrooms nationwide and is expecting to reach over 3 million students by October. The department is also planning to use Basa Pilipinas’ materials to support a countrywide teacher induction program.

Hartenberger Toby believes that DepEd’s widespread adoption of Basa Pilipinas exemplifies the importance of collaboration and a shared vision.

“Communication has been the key to building that support,” she says.

2. Use technology effectively

In 2011, Rwanda’s Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) took the bold step of making English the official language of instruction beginning in fourth grade. There was one obstacle—most primary school teachers did not have the English language skills needed to help students prepare for that transition.

Enter EDC’s USAID-funded Language, Literacy, and Learning Initiative (L3), which developed mathematics and literacy materials in both Kinyarwanda and English for students across the country. But project staff knew that materials development was only part of the solution. Teachers also needed to develop their own skills to implement the lessons.

The project turned to interactive audio instruction (IAI), developing audio-based lessons that teachers could play in class. (L3 also provided the cell phones and speakers needed to play the IAI lessons.)

IAI is an ideal professional development tool, says EDC’s Mary Sugrue, technical director for L3, because it acts as a virtual coach for teachers in the classroom, enabling learning to take place on the job. And that is an investment that continues to pay off even after the formal project ends.“In 2011, a small percentage of Rwanda’s primary school teachers were prepared to teach English to students. Since then, we’ve been able to offer professional training to tens of thousands of teachers,” says Sugrue.

3. Keep priorities on the agenda

To create programs that last in post-conflict countries where needs are great and resources are limited, it is important to keep programmatic priorities on the national agenda, says EDC’s Laura Dillon-Binkley.

As deputy chief of party for programs for the USAID Advancing Youth Project in Liberia, Dillon-Binkley has experienced this challenge firsthand. The project, which offers alternative basic education (ABE) programs to youth, has been working with the Ministry of Education to show how ABE can be integrated into the country’s educational framework.

“Liberia is a post-conflict country where everything is a priority,” she says. “Despite that, we have been successful at raising awareness at all levels of the Ministry of Education on what alternative basic education is and why it is important.”

The project has been working closely and successfully with ministry officials to map out pathways between ABE programs and the country’s formal primary, secondary, and technical and vocational schools. But in the face of competing national emergencies, support for ABE is perpetually at risk of slipping down the Ministry’s list of priorities—unless there are those who are willing to continue to fight for it.

With an eye toward long-term sustainability, the project is also building a broad base of support within communities. One example is the establishment of ABE Committees—which Dillon-Binkley equates to parent-teacher associations—to oversee ABE activities and keep the communities updated and engaged.

“The hope is communities will be able to not only keep some ABE activities going after Advancing Youth ends, but also create a more vocal demand to ensure it stays on the Ministry’s radar,” says Dillon-Binkley.